The Rebel & The Reporter

The kid enters the world of journalism

The summer of 2005 changed my life forever. After a lifetime of always being sure, so sure of the things I wanted to do and my goals, I was wallowing in deep uncertainty. Gone were the dreams I had held for a long time, the dreams of being a scientist and doing math.

I guess the reason I always wanted to be a scientist was my obsession with truth. I wanted to know. I had to know—what it is, and science seemed the best way of figuring it out. There was nothing so powerful for me as truth, and I thought it would have all the answers.

It did not. It could explain the cosmos, it could predict observances, it could peer back through billions of years to the origins of space and time—but it could not tell me anything about human beings. My single-minded pursuit of it had left me bereft of friends, alone and lonely in a place I hated.

But I still wanted to know the truth. Even depressed, on the verge of suicidal, I could not shake this obsession. I may have given up on my steed, but not on the journey. There were big questions in front of me, and I was determined to find them.

It was around that time—I think right before my flight to India in December in 2005—that I happened to pick up a biography of H.L. Mencken. It was at an airport bookstore, that magical nexus of serendipity: the meeting point between the aimlessly wandering crowd and a chance encounter with a book I judged purely by its cover, that can change a life.

I don’t know why I picked up that book. It was on the second shelf from the top, and it shouted its appeal in big bold letters. The Life and Times of Baltimore’s Bad Boy. There was a grainy photo of a man at a bar, in the middle of downing a shot, a crowd of onlookers cheering him on. His eyes are wide open, like a deer leaping straight at the camera. It’s like he got caught by surprise, doing something he thought he was doing in private.

Maybe I picked it up because that’s the kind of man I wanted to be. Notorious. Popular. Saved. The life of the party. All the things I never was, that I had for so long been so far from being.

It just so happened that he was also a journalist. It seemed like the perfect job for someone who wanted to live large while seeking out that whole set of human truths about the world that had eluded me until now. His days were a mix of writing, dictating words to someone else who transcribed them, and going out, meeting people, and drinking.

At the time, it sounded like a grand old time.

Through that trip in India, I carried that book. I don’t even know how much of it I actually read, but I remember holding onto it, sitting in the window seat, on that Kingfisher flight from Bombay to Goa, in the last row that wouldn’t recline. I didn’t feel claustrophobic. There, in the back corner of the plane, I felt snug.

So when the next summer came around, the all-important summer before senior year when internships determine the kind of jobs you’d be eligible to apply for, especially if you think like one of us Stanford kids, I made an impulsive decision. I decided I was going to become a journalist.

I probably applied to a bunch of newspapers – I definitely remember the Star-Ledger and others – that small-town, big-name mix. But none of them took me. To the contrary. I must have received 80 rejection letters. But I didn’t have a Plan B.

When you want something really bad, the Universe has a way of aligning itself to make your wins come true. I found a flyer somewhere about this journalism internship program, that the Department of Communications had. They would give $5000 to go work at a small-market newspaper that wouldn’t ordinarily be able to afford to pay interns, if it weren’t for the funding that Stanford had gotten from a guy named Reb Rebele.

The way it worked, you had to apply to the individual papers separately from the internship program. As long as you got a summer gig with one of them, the department would give you the grant separately.

There were two papers who were intrigued enough by a science nerd turned journalism wannabe that they gave me a call. The first one was a paper in Santa Monica (land of beaches and sunshine). What made you want to be a journalist? the editor down there asked. I told her about the book I’d read on H.L. Mencken. It wasn’t the kind of answer she’d expected – she was intrigued enough that she offered me the job on the spot.

Then I got a call from some guy named Tim Crewes (yes pronounced like the actor, no he doesn’t look anything like him), up in a tiny little town off the I-5 Interstate in the far north of Sacramento. Absolutely the middle of nowhere. Absolute cowville. Its claim to fame was that with 6000-odd people, it was the biggest town in the county. Which itself was the second least populous and first poorest county in California.

There was a newspaper up there called the Sacramento Valley Mirror, and I couldn’t possibly imagine what he’d have to cover. What kind of stories did they work on up there, I asked. He started talking about dogged investigative journalists, First Amendment requests, going to jail even for not giving up a source. The kind of hard-boiled reporting you expect goes on at the New York Times, not some Mirror in Podunk, California.

He could tell I was interested by what he had to say. But also on the fence. Images of Santa Monica, the beach and the waves, the girls, were still in my head. I hesitated. Get in your car and drive up and see us this weekend, he said. We’re just 5 hours away.

I don’t know how I agreed to that. I don’t even know why I followed through. But a few days later, I found myself in my little purple Civic, driving up through golden hills, the little coupe shaking any time it hit 80 mph.

The newspaper office sat at one end of Main Street. The other end was a short 8 blocks away with the title company, the county court, and the town library mainly out downtown. The real businesses sat out by the freeway, where there were a bunch of fast food stores, rest stops for the weary road truckers to make a quick pit stop before continuing on their journey.

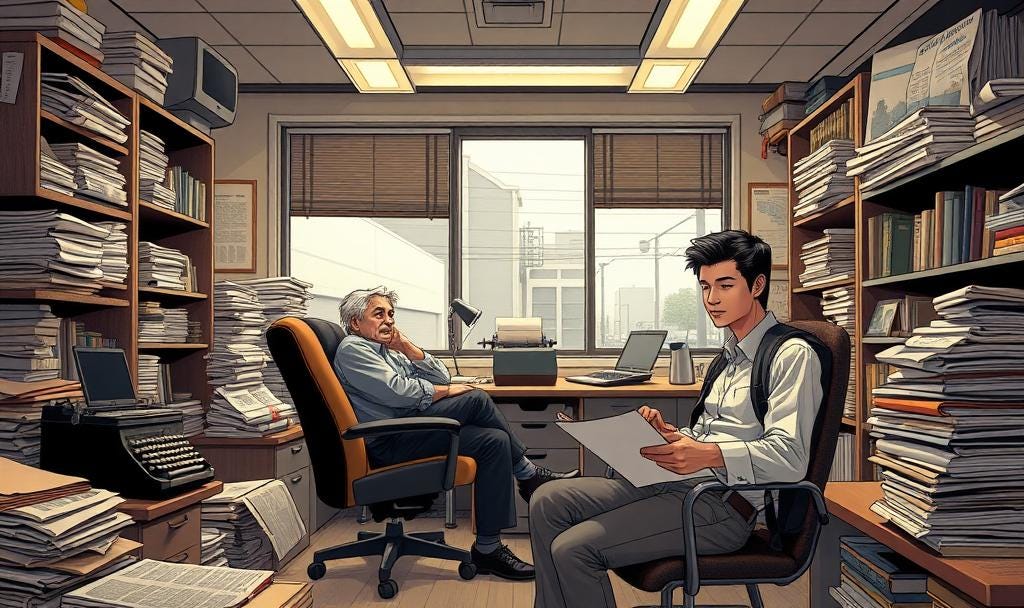

The office door made a little bell as I walked in. The office was empty, but for a white-haired man who looked an awful lot like Santa Claus. “Come on in,” he bellowed from his seat at a desk in the back. “Welcome! Welcome to the cesspool of the modern media world.” He grinned.

That day, Tim sold me on what it meant to be a journalist. A real, hard-nosed, truth-to-power, perhaps type of asshole journalist. There were books upon books of old newspaper issues lining the wall. At random, Tim would come down an aisle and start paging through — “Oh yeah, this is when we did a series on 14 articles on the shady judge and his underground business dealings. He pulled out another one – “This is when we went after the dirty cops. This place is just crawling with them.”

When I looked out the window from his little office, what I saw was a quiet street, in a quiet town that no one cared about. I saw those most coastal places when they look down at a couple hours after leaving New York en route to San Francisco. A whole lot of nothing important.

What Tim saw — what he was drawing me to — was actually that it was a dream job of a town, a place where greed and stupidity under every stone, behind every tree. The world was not simple or scientific as you think, every word is strange, weird, crazy, and full of stories. Everyone’s got one.

He had me hooked. I drove back that evening, wondering how it was that a little brown boy was giving up the sand and the surf to go apprentice himself to a crazy old white man, who promised to teach him the way the world really is.

Thank God I did, because what I learned that summer in Willows changed my life entirely. I learned how to be a journalist, how to ride a bicycle around in a Chico bar, how to write, and most of all how to see.