Priests By Another Name

The real role of priests in religion

Why do religions tend to have similar power structures?

There is almost always a layer of people above the common believer, who the common believer turns to for advice and guidance. They have gone by many names — shamans, witch doctors — but the one we know them by best are Priests.

The Priests of a religion are the people who are believed to be closer to the Sacred. They understand the sacred truths more deeply, and they have dedicated themselves to the sacred cause more fully. There is a variance in religious feeling and understanding among people, and the Priests are the ones further along the spectrum in religiosity.

This veneration yields them several critical functional roles. Their authority on the religion places them as its primary interpreters. They tell people what the religion demands of them. People actively turn to them for guidance, and unquestioningly believe the advice they’re given.

The most important interpretation is a definition of the rituals and prohibitions of the religion. These are the contact points of any religion, the place where the rubber meets the road, the moment it stops being an abstract thought experiment and idle talk to having actual, tangible effects on the world. It operates through the levers of human psychology, and the consequence of these operations are found in the actions of its believers — as guided to them by its Priests.

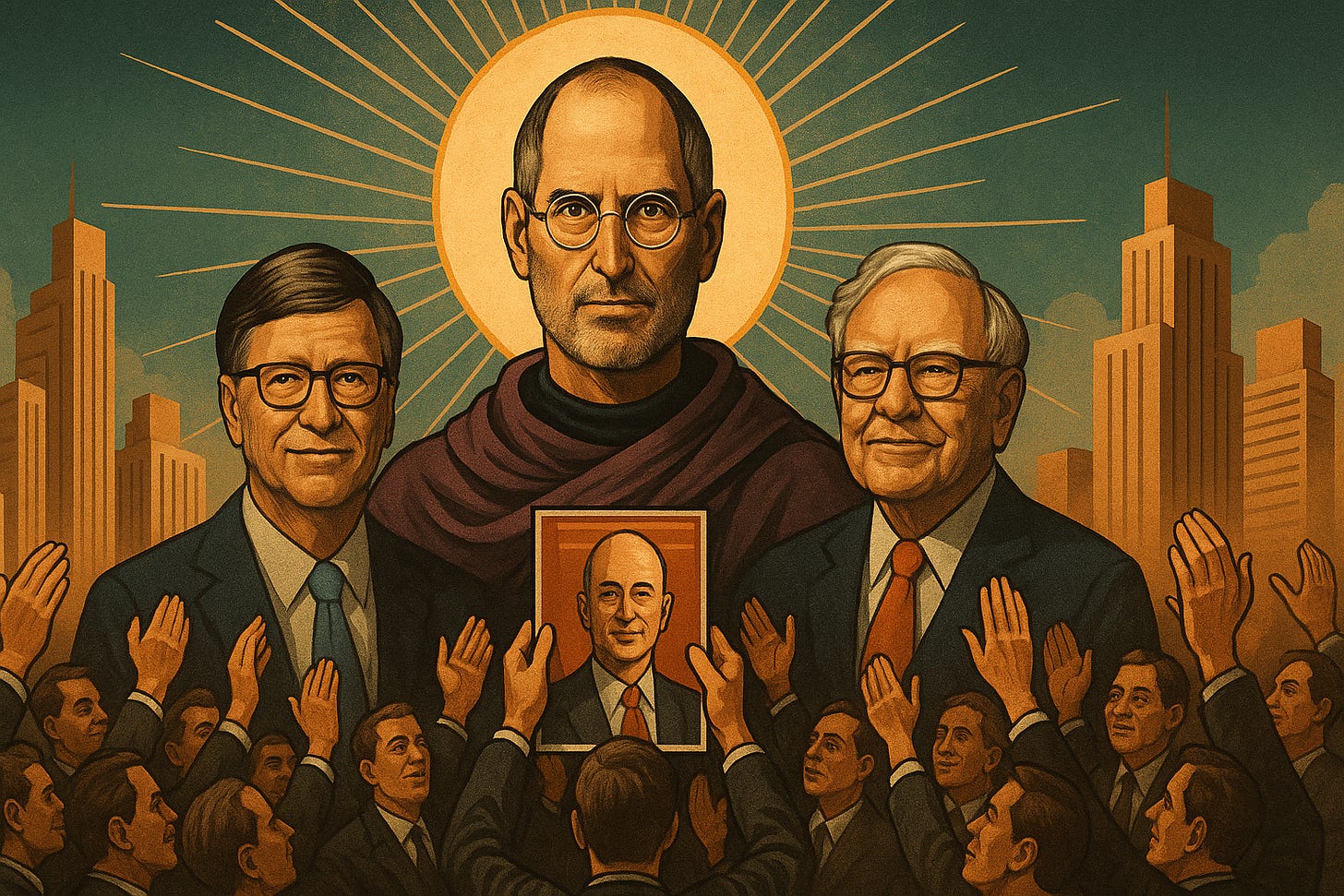

The people who we believe to be closer to the sacred truths in our modern Religion are the people who we revere and look up to because they are successful. At the uppermost levels, these are the household faces and names that grace magazine covers and receive the world’s respectful awe. But Chief among them are the rich titans of industry, whose ginormous bank balances are testimony to their understanding of the sacred mechanics that lead to Success! Or so we believe.

Everyone knows their names. Warren Buffet. Bill Gates. Steve Jobs. Jeff Bezos. Growing up, I remember the books my dad read by business leaders, trying to glean their secrets. There were always ten. They always had big pictures on the covers of an old man in a suit, staring purposefully into the camera, their name emblazoned in large, loud letters, the actual title in much smaller font, like an afterthought or a footnote.

Lee Iacocca was the one my dad carried around for years on the dashboard of our car. I remember trying to read it once on a long drive, but my brain went almost immediately numb from the jargon splayed out in front of me. What were these guys even talking about?

But as I grew older, these men and their names grew to take mythic proportions. At home, my dad and uncle would tell stories about Steve Jobs and Bill Gates as if they were only half-human, and half-divine. I remember the way they would shake their heads recounting some grand risk these wizards took, something anyone else would think was stupid, that on the surface of it seemed so utterly silly, but worked out beautifully for them in the end. Their eyes wide, they’d throw their hands up — “who would even think about taking a risk like that?”

In school, I started hearing that Bill Gates was the richest man in the world. For some reason, it was clear that this didn’t just mean that he had the most money, but something more. That he was simply the best man in the world, the one that the rest of us should one day aspire to be. What it took to get to a level like his, it was understood, was not just a few lucky breaks, but a prescience, a foresight, a genius.

Genius. The word wrapped around these great, successful men like a halo. It imbued them with a sense of majesty. A purple cloak for the modern times.

After all, the reverence given to kings of old was almost everywhere tied to religious feeling. The prostration before a secular ruler mimicked the submission of a man to the almighty divine, a man whom he could have no feeling but one of awe and uncomprehending respect. He did not know how they did it, neither god nor king — and it is in that acceptance of one’s own ignorance, it is in the chinks of the armor of faith, that the most terrible powers in human history have been made.

People killed for their king, died for their king, lived their lives by the prescriptions of their king, because they believed in their king. This kind of faith sits on a tall unassailable wall, unassailable by logic, a driver of psychology that cannot be challenged. Once you accepted the feeling of the sacred, even you accepted that some could be closer to it than others. In your own life, you even recounted the times you had been farther away and closer. The same applied, of course, to everyone else.

This distance from the sacred leads to the emergence of Priests and the powers they have. In our world, Success is the sacred, and the people who we deem successful are our Priests.

This is not just true at the level of the billionaires who we all venerate. It’s even more important at local scope. The Priests that affect our lives the most are the ones we see everyday in our corporate offices and jobs.